THUMP! goes “The Complete Earth” on my sofa. Wife Wendy is displeased because that’s her reading spot, but I’ll need a lot of space, since I have other maps and atlases deployed. Some are for boredom relief, others are relevant to our current crisis, and others are for our upcoming adventure into the Big Empty.

Even if the libraries and bookstores are closed, we have bookshelves. I’ve been going through mine and finding treasures. I’d planned to give a basic top 10 list of my favorite atlases, but as I began, I realized that would be impossible. How do you choose your favorites if you have over 100? Instead, I’ll explore how atlases enlighten us in ways that other media cannot.

Atlas was the Titan of Greek mythology who carried the world on his shoulders. That would be 13 billion trillion tons. It isn’t the weight of the Earth, but “The Complete Earth” is hefty, offering hundreds of full-color satellite images of our beautiful home at multiple scales and multiple times.

Atlases take time to absorb. We get drawn into every page. We don’t just type in a place name and zoom in, we have to find it in the book. When we do, we see everything around that place as well. As I said in a previous article, paper maps aren’t keyholes. We zoom in with our brains and eyes, not our screens.

We’re not flying right now…

However, we can still see the Earth from above. Like “The Complete Earth,” Yann Arthus-Bertrand et. al’s “Earth From Above” is a massive book, with fold-out pages that display ancient history, natural wonders, and everyday life around the globe.

Bernhard Edmaier’s “Patterns of the Earth” isn’t quite pocket-sized, but carriable. As much art as geography, it is organized thematically, with sections titled “Bands,” “Spots,” “Webs,” “Swirls” and “Spikes,” among many others, illustrating how the Earth itself is a work of art.

“To Mamie, from Rewie”

That is the handwritten inscription in my most treasured atlas, a ragged “1942 Rand McNally Ready-Reference ATLAS of the World.” More than an atlas, it is a picture of a young lady’s life during and after wartime. Inside the front cover is a pencil list of AM radio stations and ink doodles of butterflies. On nearly every page are handwritten notes, with battle sites in Europe and the Pacific circled and dated.

Another of her notes in Arizona, “double plane crash, June 30, 1956,” indicates this atlas had been in her hands for at least 14 years. That incident was the impetus for the creation of the FAA. Mamie’s atlas was a diary, a textbook, a sketchpad, and her connection with the greater world during a time of isolation.

Atlases have been read and touched.

Several years ago, I had the privilege to visit the workshop of Raven Maps and Images and Allan Cartography in Medford, Oregon. We’ve all seen their beautiful wall maps of states and countries. Stuart Allan was heading for retirement, so they were downsizing and trying to empty the office.

They generously offered me their surplus, so I took as many atlases as I could carry down the stairs. It was a fascinating glimpse into the perspective of one of our most influential modern cartographers, and a reminder that all the work we do as geographers is always based on our cartographic forbears.

In 1994, archaeology wasn’t for me anymore, so what to do? I found geography when I bought a used 18th edition “Goode’s World Atlas.” It displayed data in a way that I’d never seen, making me realize how maps reveal the world. If I could make good maps, I might be able to change the world for the better. I have used newer versions as textbooks in many courses, but Number 18, you’re always in my heart.

“It’s like an explosion in your brain.”

So says Simon, the London taxi driver. Diana Sinton and others have discussed the difference between real-time navigation and mental maps. I’ll never be as smart as a London taxi driver, but I need a journey right now after so much isolation.

The Big Empty is the vast, beautiful corner of California, Oregon and Nevada, far too big to fit on a phone. I have to get the paper out! It begins as a mess of maps, atlases and pens. Reckless as I am, I don’t want to pull out maps and atlases while I’m driving, so I need a good mental map.

As I explore these different maps, each of which reveal the same places at different scales and tell different stories, I develop a geographic perspective that scales down to smaller pictures. Just turn left at the windmill.

“Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”

That dark quote is from George Orwell’s dystopian novel “1984,” in which history is revised on a daily basis. Geography doesn’t just reveal space, it reveals changes over time. Using a map app, we see the world in that moment only. Geographic reality can be changed by parties unknown.

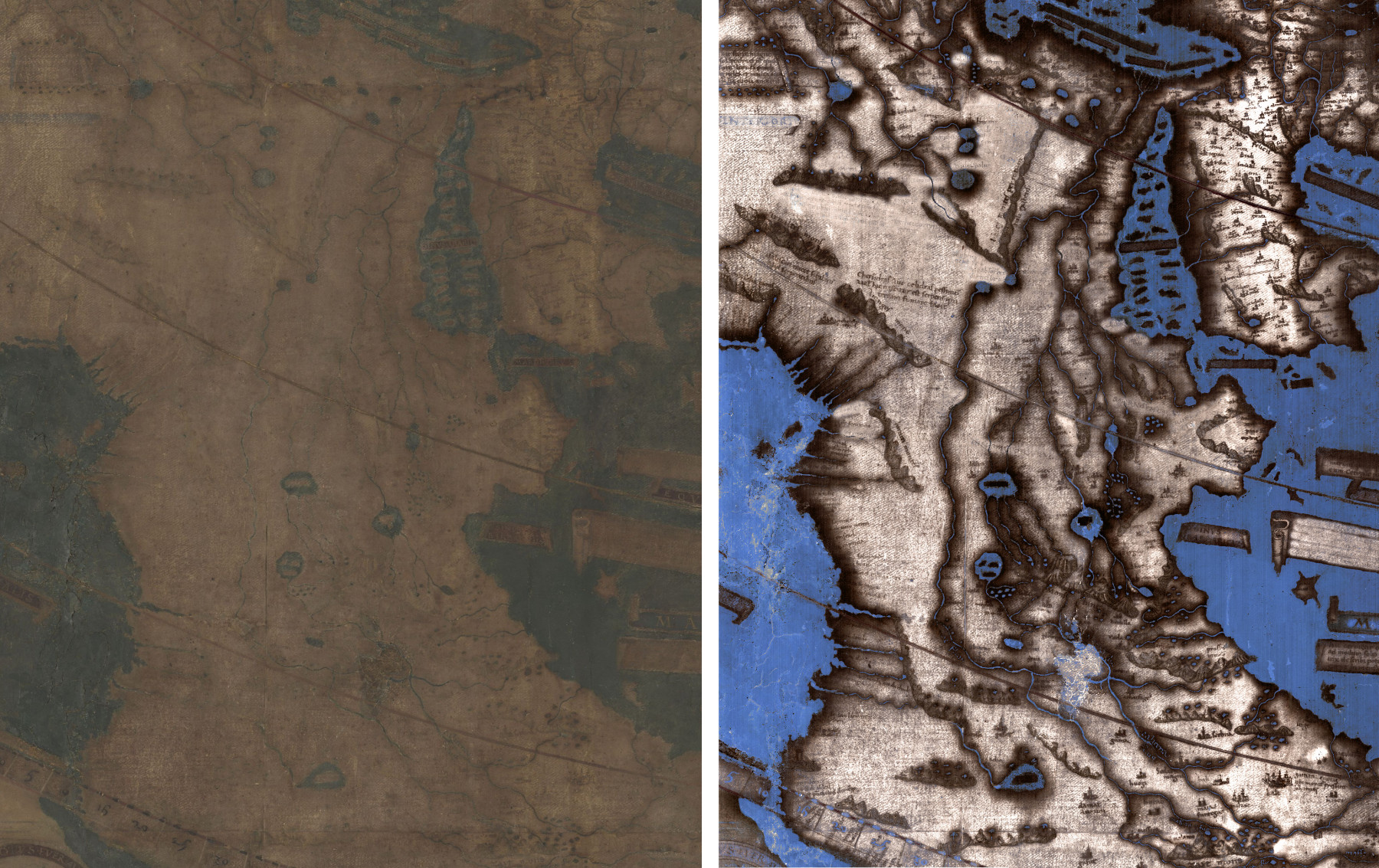

My oldest atlas is from 1909, a geography textbook. There was no Panama Canal. Before air travel, the immense island of New Guinea was unexplored and unmapped. Neither world war had happened, but there were portents. Then “Goode’s World Atlas” from 1946 shows the geopolitics of the world just after one of the most significant events in modern history. A stack of atlases, cumbersome as they may be, tells stories through time.

“Fifty Islands I Have Never Set Foot On And Never Will.”

That is the subtitle of Judith Schalansky’s “Atlas of Remote Islands.” As we shelter in place, we realize that we’ll never see every place on Earth. Yet every map of every place can tell a unique story of a unique place and take us there. In “Another America: Native American Maps and the History of Our Land,” Mark Warhus shows us familiar places mapped from a very different perspective, some on paper, some on bison hides.

William Hornaday shocked Americans with his depiction of the rapid decline of the bison after the Civil War, which helped spur the modern conservation ethic. Included in Susan Schulten’s “A History of America in 100 Maps,” it is one of 99 others that illustrate how history is written in maps, and also how maps can write history.

Every atlas offers a different perspective. “Brilliant Maps: An Atlas for Curious Minds“, “The Penguin State of the World Atlas,” and “Atlas of the Real World” blend cartography and infographics. The latter, for example, uses cartograms to distort the land areas of the world based on thematic data such as electricity access and spending on tourism.

THUMP! goes the atlas in the classroom!

Seminal in map-based infographics are the works of Edward Tufte. After attending one of his trainings, in which his three books were the primary curriculum, I used this same technique teaching an archaeology course. Tufte’s books are based on page pairs, with two facing pages each delivering a lesson.

Instead of a textbook, I taught from “Past Worlds: Collins Atlas of Archaeology.” Students laid out their books (THUMP!) as we discussed topics on specific pages. Page pairs made teaching from an atlas not only effective, but far more engaging than slides on a screen. These were their own books—they could make notes, draw on them, doodle like Mamie. When they left, the book was theirs to keep.

The third-grade class at Sage School will also have their book to keep. They wrote “The Klamath Agency: Stories of the Past,” interviewing Klamath tribal elders and making a map that reconstructed the Agency as it was in the 1940s. Most of the buildings they mapped are gone, but they created a record of the past that can be passed on to the future. Years later, these kids can pull their work off the bookshelf. Stories told by elders long passed will still be in their hands.

I could go on and on, page by page…

Obviously, I love atlases. Every individual copy has a story, but not just the information it offers. This one led me to my wife, this one changed a kid’s life, I helped edit this one, I bonded with a colleague looking at this one…

Books offer a sense of permanency. They can smell fresh-off-the-press or they can smell like generations of readers before us. The pages may sound crisp and new or they may sound dangerously close to turning to dust. Like Mamie’s 1942 atlas, maps, books and atlases connect us with the greater world.

Whether you’re exploring map treasures virtually or have the honor of owning a few collections, take this strange time to go exploring from your sofa. With an atlas, you can relive past adventures and plan new ones, visit places you’ll never go, and explore the same world from vastly different perspectives.